Moneylife: Ahmedabad: Wednesday, 22 January 2025.

Suraj Damor (name changed), 26, first began migrating to Ahmedabad from Jhabua district in Madhya Pradesh when he was 17 years old. Initially Damor, a Bhil Adivasi, would find daily wage construction work at labour nakas. In 2016, a relative told him about the opportunity of driving a door-to-door waste collection vehicle in Ahmedabad, which would assure him secure employment in comparison to the daily grind of seeking work at the naka. It also meant he could work with this wife, and take their child along in the vehicle.

Many urban local bodies (ULBs) in India collect residential and commercial waste door-to-door, and transfer it directly to Material Recovery Facilities, a solution to the problem of ever-mounting waste. In 2021-22, as per the latest report from the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), urban India generated more than 62 million tonnes of solid waste annually, of which about 57.1 million tonnes was collected, and around 33.4 million tonnes processed.

Damor was hired by a private company in Ahmedabad which held the tender for door-to-door waste collection from the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation. Most workers from his Basti worked with two contractors–Om Swachatha Corporation and Jigar Transport Company but Damor did not want to name the company he worked for. After four years, Damor and his wife were fired for objecting that the costs of vehicle maintenance were transferred onto the workers.

This mirrors the experiences of other tribal migrant workers engaged in door-to-door waste collection in Ahmedabad, Gandhinagar and Surat, evidenced in a research study conducted by the Centre for Labour Research and Action, a rights-based NGO. The survey found that the workers were not receiving the government-mandated minimum wages for unskilled labour, over half were not part of social security programmes and over 60% did not receive any protective gear for waste collection.

The findings of the research are based on a survey of and focus group discussions with 196 tribal worker families between August and October 2023, who were generally hired in pairs, with the husband working as a driver and the woman engaged in waste collection and segregation.

Changing workforce and migration patterns

In Surat, door-to-door waste collection began in the early 2000s. The responsibility of collecting the waste from households and commercial units was handed over to private entities from the beginning. As the work got outsourced, historical waste-picking communities were impacted with their work being contracted to companies, per a study conducted by Vimal Trivedi, a professor at the Centre for Social Studies, Surat, as part of a mid-term evaluation of the waste collection system by the Surat Municipal Corporation.

In Ahmedabad too, privatisation of the waste collection system led to the displacement of women from the Dalit community, who have been working as informal waste collectors in the city.

According to a 2024 report, the Surat Municipal Corporation had a dedicated fleet of 575 vehicles for door-to-door waste collection. This would translate to at least 1,150 workers, as there are at least two workers per vehicle. Ahmedabad has more than 1,000 vehicles and Gandhinagar has more than 50 vehicles.

In Surat, Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar, tribal migrants have entered the waste management domain in recent years, and were earlier migrating for construction work. Of the 196 families surveyed, 73% took up this work within the last five years from the time of the survey in 2023. As many as 86% of the workers were between 18 and 30 years old, indicating a young workforce. Over half (62%) of the workers said that they had not received any formal schooling, indicating a mostly illiterate workforce.

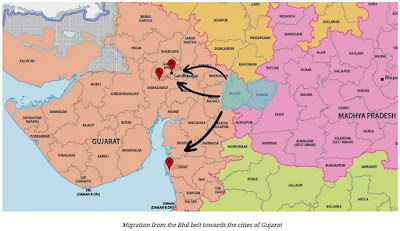

Seventy-two percent of the workers were from Jhabua in Madhya Pradesh, and 21% belonged to Dahod in Gujarat. These regions form part of the Bhil tribal belt, from where seasonal migration has been increasing over the years due to unproductive and small landholdings, depriving the tribal population of any source of livelihood, and pushing them to migrate. With the nature of seasonal migration changing over the years, the workers spend more than 10 months at the destination on average, and only travel back to their source villages during festivals or in an emergency, as per the survey.

The workers said that their existing networks played a crucial role in migrating, as mukaddams or labour contractors from their villages or adjacent villages facilitated their entry into this work. There is often a chain of contractors between the worker and the private company who has the tender for waste collection. Some of the contractors are also engaged in this work.

Workers shared that the possibility of receiving regular wages, additional income from scrap sales which enable savings for contingencies, and an opportunity for the couple to work together while taking the children along with them in the vehicle, contributed towards their transition into waste collection work.

Unfavourable working conditions

The tribal workers engaged in door-to-door waste collection are usually hired in pairs. In some cases in Surat, the vehicle had three workers a driver (usually a male), and two helpers (mostly women). In Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar, each vehicle had two workers he husband and wife.

The survey found that the workers were not receiving the government-mandated minimum wages for ‘unskilled’ labour in these cities. The wages paid to the workers ranged from Rs 200 to Rs 333 per day per person for 30 days of work, which was lower than the minimum wage of Rs 452 per day for unskilled work in 2023.

Moreover, monthly wages differ depending on the weight of the waste collected in some cases. For instance, workers in the Bhestan area of Surat reported that their wages were purely dependent on the volume of the waste that was collected.

The research found that this practice of underpaying workers continues because of the absence of formal employment contracts. Workers were mostly hired verbally and required to report to the supervisors from the contracted companies, who rarely conduct any monitoring or training.

Payment frequency also differed, as some workers said they received wages on the 15th of every month, while others said they received it every two months. Further, for 56% of workers the payments were in cash, while for 41%, the wages were deposited in their bank accounts, but they said they did not have access to their passbooks or ATM cards, which were held by the contractors. Cash was withdrawn from their accounts by the contractors and handed over to the workers.

The workers can also earn an additional daily income of Rs 150 to Rs 400 from sorting and selling scrap. The woman’s labour is a major contributor towards earning this income as she is the one sorting through the garbage under precarious conditions, often in a moving vehicle. However, her labour is often invisibilised as she does not receive any direct payment for her work. In Surat, workers informed us that they had not received salaries for over six months and were surviving on scrap sales.

We tried reaching out to the contracting agencies but there were no phone numbers or email addresses available publicly for these agencies other than Om Swachchata Corporation. We tried reaching out to sub-contractors and supervisors using phone numbers provided by the workers union, but have been unable to reach these companies for comment.

We reached out to the Solid Waste Management Departments of Surat, Ahmedabad, and Gandhinagar, Om Swachatha Corporation and Darbar Waste Corporation via email, requesting comment on the research findings, and will update the story when we receive a response.

Fifty-six per cent of the workers surveyed reported that they did not receive any kind of social security benefits such as provident fund (PF), medical insurance or pension, despite the hazardous nature of their work. Nearly a third (30%) of the workers reported that they received PF but did not know the amount that was deposited per month nor did they have the UAN or Universal Account Number that can be used to access the PF account. In some cases, Rs 500 to Rs 1,000 was deducted by the contractors as PF, before cash was handed over to the workers.

For the majority, the workday stretched beyond eight hours, averaging at around 11 hours. Many workers reported leaving for work at 4 a.m. They worked without any weekly off, which goes against the terms of the contract between the Gandhinagar Municipal Corporation and the contracted entity–Darbar Waste Corporation–in this case. The contract was sourced by CLRA through a Right to Information (RTI) request to the Gandhinagar Municipal Corporation. The workers reported that even when they have to travel to their villages during festivals, they have to keep a replacement worker and part with the wages for that period, consequently making it an unpaid leave.

Sixty-five per cent of the workers said they did not receive any protective gear like hand gloves, masks, boots, etc. Some of the workers who received the gear reported that the gloves were made of poor-quality cloth and deteriorated when they came in contact with wet waste, and suggested that they be provided rubber gloves.

The lack of quality protective gear is particularly dangerous for women workers as they are the ones sifting through the waste to find scrap for sale. The waste, mostly unsegregated, contains diverse materials such as food waste, sanitary waste, broken glass and medical waste leading to cuts and injuries. This situation gets exacerbated due to 98% of the workers not receiving any training, the survey found.

Health issues such as fever, body pain, stomach infections, and skin and breathing issues were common among the workers, leading to out-of-pocket expenses, as workers said they prefer private healthcare over government hospitals and clinics which do not adequately cater to their needs.

None of the workers said they had health insurance, nor were there any instances of health camps being organised by the municipal corporations or the contracted company. Further, none of the women surveyed reported receiving any maternity benefits. The burden of child-rearing, along with other domestic burdens, also exclusively fell on them as they find it hard to access government-run anganwadis or schools, because either facilities are too far from their place of residence, or they lack documentation to enrol their children.

The precarious living conditions of workers

The workers stay in squatter settlements or bastis which are usually close to the waste transfer stations, where the waste collected from the respective zone by the door-to-door collection vehicles is transported, segregated and then transported again to the landfill. They reside on land provided by the contractor, which is also used as a parking spot for the vehicles.

Ninety-four percent of the surveyed families said that they reside in kutcha houses made of tarpaulin and bamboo, and 91% of the workers staying in these squatter settlements do not have access to toilets. Water access is also limited, with reliance on water tankers and private taps. Workers said that they face water-logging during rains and extreme heat during the summer months, impacting their general well-being.

In focus group discussions, workers also said they faced discrimination from urban residents, who, they said, held a negative perception of their work being “dirty”. Consequently, the workers have made peace with staying in these settlements, as they often are not accepted in other areas.

Role of urban local bodies

The responsibility of implementing labour laws lies with the contracting agency and not the municipal corporation, as per one of the contracts, accessed through the RTI Act, between Gandhinagar Municipal Corporation and the contracted agency, Darbar Waste Corporation.

The contract reads, “the Contractor shall act as prime employer for all the manpower employed for the proposed work. The persons employed by the Contractor shall not in any case be treated as employees of the Employer nor is the Employer answerable to the Contractor’s staff.” It adds that the “Contractor shall be solely responsible for the payment of wages / salary along with extending benefits such as Provident Fund (PF), Insurance, Bonus, etc. in accordance with the applicable Labour Welfare Act and Laws”.

This runs counter to provisions of the Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970 according to which the principal employer, which in this case is the ULB, is obligated to provide amenities and wages to the workers in case the contractor fails to do so.

CLRA also filed an RTI request in Ahmedabad, and an appeal after receiving no response to the original request. The RTI request is still pending. No RTI request was filed in Surat.

In addition, the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016 does not have substantial clauses on the rights of waste collection workers or safeguards available to them. The rules, which say that local authorities are responsible for facilitating “construction, operation and maintenance of solid waste processing facilities and associated infrastructure on their own or with private sector participation or through any agency for optimum utilisation of various components of solid waste adopting suitable technology” have led to the contractualisation of work to private actors and threatened the security of livelihood for the workers, experts say.

Further, according to the Assistant Labour Commissioner of Ahmedabad, as reported by the Indian Express, “the labour department does not have powers to suo motu conduct inspection of work sites and is empowered to take action only if a complaint is filed”.

According to Denis Macwan of the Majur Adhikar Manch, a trade union working with unorganised workers in Gujarat, local Dalit workers employed directly with municipal corporations were more vocal about their rights regarding wages and working conditions, and demanded shorter working hours and regular leave. “Consequently (private companies) began hiring migrant workers…The migration-induced vulnerabilities are critical for private companies as wages can be kept low and workers can be made to work for longer hours.” Contractualisation thus, makes it more difficult for workers to demand their rights.

“Door-to-door waste collection workers in metro cities of Gujarat represent an intersection of multiple vulnerabilities--tribal, female, seasonal migrants, and engaged in a task that is historically considered demeaning,” says Sudhir Katiyar, founder of CLRA. “Door-to-door waste collection is an essential service that has to be performed daily. Therefore, contract labour should not be permitted at all. Even when permitted, the workers are not regulated as per the provisions of the Act. They have no written contract, do not receive minimum wages, work long hours without overtime, and have inadequate social security.”

Way forward

In January 2024, at the Swachh Survekshan Award organised by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Gujarat’s Surat was adjudged the cleanest city in India, sharing the spot with Indore, Madhya Pradesh. But awards ignore the precarious existence of the humans who put their health and well being at risk for Swachh Bharat.

Tribal migrants now face the same conditions as those Scheduled Caste groups who have historically been performing this labour in both urban and rural areas. Workers said that unionising would help them in collectively putting forward their issues and demands. They mentioned identity cards issued by a municipal corporation as a way to establish their identity as a worker.

There are some examples where informal waste pickers have been integrated into the formal waste collection system.

In Bengaluru, through the intervention of NGO Hasiru Dala, informal waste pickers were integrated into the dry waste collection centers.

Through sustained advocacy, Kagad Kach Patra Kashtakari Panchayat (KKPKP), a trade union in Pune of waste pickers collecting paper, glass and metal, organised in the 1990’s to be recognised by the Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) and demand better working conditions. In 2008, this union integrated informal recyclers into the formal system through a worker-led cooperative called SWaCH. They were authorised by the PMC to collect segregated waste from households and commercial establishments.

Even when waste pickers were not given a direct contract by the municipal corporation, such as in Pimpri Chinchwad, the presence of the union ensured that existing waste pickers were hired by private entities and also ensured their accountability towards the workers. It also helped workers win a minimum wage-related case in 2024, resulting in a payment of Rs 7.5 crore to 310 waste pickers employed by the Pimpri Chinchwad Municipal Corporation.

Despite these wins, SWaCH has to periodically negotiate with the PMC for renewal, faces competition from other private parties, and workers still face challenges given the contractual nature of the arrangement with the municipal corporation.

Organising workers and ending the system of contractualisation for essential municipal work are some measures to improve working conditions, said Macwan. Moreover, he said, the state should ensure education for their children to enable social mobility.

“Municipal authorities should ensure the continuation of the workforce even when there is a change in contractor. This will ensure a modicum of security that will provide workers with a platform from where they can secure their other rights,” says Katiyar.

Suraj Damor (name changed), 26, first began migrating to Ahmedabad from Jhabua district in Madhya Pradesh when he was 17 years old. Initially Damor, a Bhil Adivasi, would find daily wage construction work at labour nakas. In 2016, a relative told him about the opportunity of driving a door-to-door waste collection vehicle in Ahmedabad, which would assure him secure employment in comparison to the daily grind of seeking work at the naka. It also meant he could work with this wife, and take their child along in the vehicle.

Many urban local bodies (ULBs) in India collect residential and commercial waste door-to-door, and transfer it directly to Material Recovery Facilities, a solution to the problem of ever-mounting waste. In 2021-22, as per the latest report from the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), urban India generated more than 62 million tonnes of solid waste annually, of which about 57.1 million tonnes was collected, and around 33.4 million tonnes processed.

Damor was hired by a private company in Ahmedabad which held the tender for door-to-door waste collection from the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation. Most workers from his Basti worked with two contractors–Om Swachatha Corporation and Jigar Transport Company but Damor did not want to name the company he worked for. After four years, Damor and his wife were fired for objecting that the costs of vehicle maintenance were transferred onto the workers.

This mirrors the experiences of other tribal migrant workers engaged in door-to-door waste collection in Ahmedabad, Gandhinagar and Surat, evidenced in a research study conducted by the Centre for Labour Research and Action, a rights-based NGO. The survey found that the workers were not receiving the government-mandated minimum wages for unskilled labour, over half were not part of social security programmes and over 60% did not receive any protective gear for waste collection.

The findings of the research are based on a survey of and focus group discussions with 196 tribal worker families between August and October 2023, who were generally hired in pairs, with the husband working as a driver and the woman engaged in waste collection and segregation.

Changing workforce and migration patterns

In Surat, door-to-door waste collection began in the early 2000s. The responsibility of collecting the waste from households and commercial units was handed over to private entities from the beginning. As the work got outsourced, historical waste-picking communities were impacted with their work being contracted to companies, per a study conducted by Vimal Trivedi, a professor at the Centre for Social Studies, Surat, as part of a mid-term evaluation of the waste collection system by the Surat Municipal Corporation.

In Ahmedabad too, privatisation of the waste collection system led to the displacement of women from the Dalit community, who have been working as informal waste collectors in the city.

According to a 2024 report, the Surat Municipal Corporation had a dedicated fleet of 575 vehicles for door-to-door waste collection. This would translate to at least 1,150 workers, as there are at least two workers per vehicle. Ahmedabad has more than 1,000 vehicles and Gandhinagar has more than 50 vehicles.

In Surat, Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar, tribal migrants have entered the waste management domain in recent years, and were earlier migrating for construction work. Of the 196 families surveyed, 73% took up this work within the last five years from the time of the survey in 2023. As many as 86% of the workers were between 18 and 30 years old, indicating a young workforce. Over half (62%) of the workers said that they had not received any formal schooling, indicating a mostly illiterate workforce.

Seventy-two percent of the workers were from Jhabua in Madhya Pradesh, and 21% belonged to Dahod in Gujarat. These regions form part of the Bhil tribal belt, from where seasonal migration has been increasing over the years due to unproductive and small landholdings, depriving the tribal population of any source of livelihood, and pushing them to migrate. With the nature of seasonal migration changing over the years, the workers spend more than 10 months at the destination on average, and only travel back to their source villages during festivals or in an emergency, as per the survey.

The workers said that their existing networks played a crucial role in migrating, as mukaddams or labour contractors from their villages or adjacent villages facilitated their entry into this work. There is often a chain of contractors between the worker and the private company who has the tender for waste collection. Some of the contractors are also engaged in this work.

Workers shared that the possibility of receiving regular wages, additional income from scrap sales which enable savings for contingencies, and an opportunity for the couple to work together while taking the children along with them in the vehicle, contributed towards their transition into waste collection work.

Unfavourable working conditions

The tribal workers engaged in door-to-door waste collection are usually hired in pairs. In some cases in Surat, the vehicle had three workers a driver (usually a male), and two helpers (mostly women). In Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar, each vehicle had two workers he husband and wife.

The survey found that the workers were not receiving the government-mandated minimum wages for ‘unskilled’ labour in these cities. The wages paid to the workers ranged from Rs 200 to Rs 333 per day per person for 30 days of work, which was lower than the minimum wage of Rs 452 per day for unskilled work in 2023.

Moreover, monthly wages differ depending on the weight of the waste collected in some cases. For instance, workers in the Bhestan area of Surat reported that their wages were purely dependent on the volume of the waste that was collected.

The research found that this practice of underpaying workers continues because of the absence of formal employment contracts. Workers were mostly hired verbally and required to report to the supervisors from the contracted companies, who rarely conduct any monitoring or training.

Payment frequency also differed, as some workers said they received wages on the 15th of every month, while others said they received it every two months. Further, for 56% of workers the payments were in cash, while for 41%, the wages were deposited in their bank accounts, but they said they did not have access to their passbooks or ATM cards, which were held by the contractors. Cash was withdrawn from their accounts by the contractors and handed over to the workers.

The workers can also earn an additional daily income of Rs 150 to Rs 400 from sorting and selling scrap. The woman’s labour is a major contributor towards earning this income as she is the one sorting through the garbage under precarious conditions, often in a moving vehicle. However, her labour is often invisibilised as she does not receive any direct payment for her work. In Surat, workers informed us that they had not received salaries for over six months and were surviving on scrap sales.

We tried reaching out to the contracting agencies but there were no phone numbers or email addresses available publicly for these agencies other than Om Swachchata Corporation. We tried reaching out to sub-contractors and supervisors using phone numbers provided by the workers union, but have been unable to reach these companies for comment.

We reached out to the Solid Waste Management Departments of Surat, Ahmedabad, and Gandhinagar, Om Swachatha Corporation and Darbar Waste Corporation via email, requesting comment on the research findings, and will update the story when we receive a response.

Fifty-six per cent of the workers surveyed reported that they did not receive any kind of social security benefits such as provident fund (PF), medical insurance or pension, despite the hazardous nature of their work. Nearly a third (30%) of the workers reported that they received PF but did not know the amount that was deposited per month nor did they have the UAN or Universal Account Number that can be used to access the PF account. In some cases, Rs 500 to Rs 1,000 was deducted by the contractors as PF, before cash was handed over to the workers.

For the majority, the workday stretched beyond eight hours, averaging at around 11 hours. Many workers reported leaving for work at 4 a.m. They worked without any weekly off, which goes against the terms of the contract between the Gandhinagar Municipal Corporation and the contracted entity–Darbar Waste Corporation–in this case. The contract was sourced by CLRA through a Right to Information (RTI) request to the Gandhinagar Municipal Corporation. The workers reported that even when they have to travel to their villages during festivals, they have to keep a replacement worker and part with the wages for that period, consequently making it an unpaid leave.

Sixty-five per cent of the workers said they did not receive any protective gear like hand gloves, masks, boots, etc. Some of the workers who received the gear reported that the gloves were made of poor-quality cloth and deteriorated when they came in contact with wet waste, and suggested that they be provided rubber gloves.

The lack of quality protective gear is particularly dangerous for women workers as they are the ones sifting through the waste to find scrap for sale. The waste, mostly unsegregated, contains diverse materials such as food waste, sanitary waste, broken glass and medical waste leading to cuts and injuries. This situation gets exacerbated due to 98% of the workers not receiving any training, the survey found.

Health issues such as fever, body pain, stomach infections, and skin and breathing issues were common among the workers, leading to out-of-pocket expenses, as workers said they prefer private healthcare over government hospitals and clinics which do not adequately cater to their needs.

None of the workers said they had health insurance, nor were there any instances of health camps being organised by the municipal corporations or the contracted company. Further, none of the women surveyed reported receiving any maternity benefits. The burden of child-rearing, along with other domestic burdens, also exclusively fell on them as they find it hard to access government-run anganwadis or schools, because either facilities are too far from their place of residence, or they lack documentation to enrol their children.

The precarious living conditions of workers

The workers stay in squatter settlements or bastis which are usually close to the waste transfer stations, where the waste collected from the respective zone by the door-to-door collection vehicles is transported, segregated and then transported again to the landfill. They reside on land provided by the contractor, which is also used as a parking spot for the vehicles.

Ninety-four percent of the surveyed families said that they reside in kutcha houses made of tarpaulin and bamboo, and 91% of the workers staying in these squatter settlements do not have access to toilets. Water access is also limited, with reliance on water tankers and private taps. Workers said that they face water-logging during rains and extreme heat during the summer months, impacting their general well-being.

In focus group discussions, workers also said they faced discrimination from urban residents, who, they said, held a negative perception of their work being “dirty”. Consequently, the workers have made peace with staying in these settlements, as they often are not accepted in other areas.

Role of urban local bodies

The responsibility of implementing labour laws lies with the contracting agency and not the municipal corporation, as per one of the contracts, accessed through the RTI Act, between Gandhinagar Municipal Corporation and the contracted agency, Darbar Waste Corporation.

The contract reads, “the Contractor shall act as prime employer for all the manpower employed for the proposed work. The persons employed by the Contractor shall not in any case be treated as employees of the Employer nor is the Employer answerable to the Contractor’s staff.” It adds that the “Contractor shall be solely responsible for the payment of wages / salary along with extending benefits such as Provident Fund (PF), Insurance, Bonus, etc. in accordance with the applicable Labour Welfare Act and Laws”.

This runs counter to provisions of the Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970 according to which the principal employer, which in this case is the ULB, is obligated to provide amenities and wages to the workers in case the contractor fails to do so.

CLRA also filed an RTI request in Ahmedabad, and an appeal after receiving no response to the original request. The RTI request is still pending. No RTI request was filed in Surat.

In addition, the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016 does not have substantial clauses on the rights of waste collection workers or safeguards available to them. The rules, which say that local authorities are responsible for facilitating “construction, operation and maintenance of solid waste processing facilities and associated infrastructure on their own or with private sector participation or through any agency for optimum utilisation of various components of solid waste adopting suitable technology” have led to the contractualisation of work to private actors and threatened the security of livelihood for the workers, experts say.

Further, according to the Assistant Labour Commissioner of Ahmedabad, as reported by the Indian Express, “the labour department does not have powers to suo motu conduct inspection of work sites and is empowered to take action only if a complaint is filed”.

According to Denis Macwan of the Majur Adhikar Manch, a trade union working with unorganised workers in Gujarat, local Dalit workers employed directly with municipal corporations were more vocal about their rights regarding wages and working conditions, and demanded shorter working hours and regular leave. “Consequently (private companies) began hiring migrant workers…The migration-induced vulnerabilities are critical for private companies as wages can be kept low and workers can be made to work for longer hours.” Contractualisation thus, makes it more difficult for workers to demand their rights.

“Door-to-door waste collection workers in metro cities of Gujarat represent an intersection of multiple vulnerabilities--tribal, female, seasonal migrants, and engaged in a task that is historically considered demeaning,” says Sudhir Katiyar, founder of CLRA. “Door-to-door waste collection is an essential service that has to be performed daily. Therefore, contract labour should not be permitted at all. Even when permitted, the workers are not regulated as per the provisions of the Act. They have no written contract, do not receive minimum wages, work long hours without overtime, and have inadequate social security.”

Way forward

In January 2024, at the Swachh Survekshan Award organised by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Gujarat’s Surat was adjudged the cleanest city in India, sharing the spot with Indore, Madhya Pradesh. But awards ignore the precarious existence of the humans who put their health and well being at risk for Swachh Bharat.

Tribal migrants now face the same conditions as those Scheduled Caste groups who have historically been performing this labour in both urban and rural areas. Workers said that unionising would help them in collectively putting forward their issues and demands. They mentioned identity cards issued by a municipal corporation as a way to establish their identity as a worker.

There are some examples where informal waste pickers have been integrated into the formal waste collection system.

In Bengaluru, through the intervention of NGO Hasiru Dala, informal waste pickers were integrated into the dry waste collection centers.

Through sustained advocacy, Kagad Kach Patra Kashtakari Panchayat (KKPKP), a trade union in Pune of waste pickers collecting paper, glass and metal, organised in the 1990’s to be recognised by the Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) and demand better working conditions. In 2008, this union integrated informal recyclers into the formal system through a worker-led cooperative called SWaCH. They were authorised by the PMC to collect segregated waste from households and commercial establishments.

Even when waste pickers were not given a direct contract by the municipal corporation, such as in Pimpri Chinchwad, the presence of the union ensured that existing waste pickers were hired by private entities and also ensured their accountability towards the workers. It also helped workers win a minimum wage-related case in 2024, resulting in a payment of Rs 7.5 crore to 310 waste pickers employed by the Pimpri Chinchwad Municipal Corporation.

Despite these wins, SWaCH has to periodically negotiate with the PMC for renewal, faces competition from other private parties, and workers still face challenges given the contractual nature of the arrangement with the municipal corporation.

Organising workers and ending the system of contractualisation for essential municipal work are some measures to improve working conditions, said Macwan. Moreover, he said, the state should ensure education for their children to enable social mobility.

“Municipal authorities should ensure the continuation of the workforce even when there is a change in contractor. This will ensure a modicum of security that will provide workers with a platform from where they can secure their other rights,” says Katiyar.