The Wire: National: Tuesday, 6 August 2024.

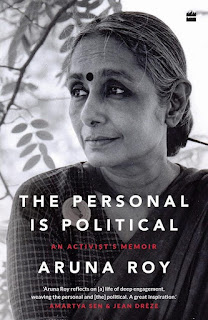

The memoir 'The Personal is Political' brings the many shades of the activist to light besides offering insights to new generations to look for macro solutions while getting involved in field-level action.

When I pre-ordered my copy of Aruna Roy’s memoir, there was more to it than just a desire for a ‘good’ read. I had spent the first few years of the 21st century working in Rajasthan, with Aruna, on the National Campaign for the People’s Right to Information (NCPRI). In these years, my learning curve was very steep and led me on a journey of social change that I am still part of. So, to read the memoir was a natural desire; but to convince myself to go to the India International Centre for the book release on July 4 was more of a challenge. For one, it meant a two-hour journey from Gurgaon in auto-rickshaws and the Metro, and second, I felt I had seen this life and in some small way had even been part of it. In my smugness, I thought I would have nothing new to gain. Finally, when I did decide to go, I told myself it was only as an act of solidarity. I was pleasantly surprised to be refreshed and re-energised by the discussion that day.

After the book release, as we sat talking, there was a lot of remembering my days with Aruna and the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS), the collective Aruna co-founded. I met a lot of people, some whom I had known as part of my days in Rajasthan, and a larger, eclectic group of people who came from all walks of life – retired civil servants, lawyers, filmmakers, journalists, academics, activists and comrades. But what was the real icing on the cake was to be able to hear the panel discussion, moderated by Ankita Anand, a poet and independent journalist. The panel included powerful women, senior journalist Pamela Philipose, writer Natasha Badhwar and political scientist Niraja Jayal, besides Aruna herself. The sole man on the panel, the writer, literary critic and retired bureaucrat Ashok Vajpayee was also impressive.

As we entered the hall where the book release was to happen, I was expecting the aesthetics, the paintings next to the dais, the beautifully designed backdrop. These were all very ‘Aruna’. But what I was not prepared for was the absence of Aruna’s women friends: Naurati Bai, Chunni Bai, Susheela Bai and many others, who are her co-travelers and who populate the pages of her memoir. However, as the evening progressed, it was clear that all those who were absent were actually present in spirit, and the hall resonated with their stories and a collective journey.

Each panelist brought to life an Aruna we know collectively the one who is an activist and the one who is a connoisseur of classical music. In her many shades, we are as likely to have seen Aruna clad in a handwoven sari, gifted to her by family and friends, protesting at the local administrative office with her friends from rural Rajasthan, as to have seen her enjoying an evening of Indian classical music with people of ‘high’ culture.

She is also the same Aruna who puts on classical music or a selection of folk or bhakti music by the Langa and Mangniyars and walks around the house meditatively putting things in order. Her sense of aesthetics has in no way been compromised by her declassed activist life; whether it be Devdungri or Tilonia, both places that she cohabits with her collective, everyone benefits from her aesthetic sense. This, then, makes it no surprise that her memoir is strewn with quotations from Blake, Tagore, Yeats, Shakespeare, Victor Hugo and many other literary figures. At the same time, you find in her writing the folk wisdom of Kabir, Lao Tzu, Vijay Dan Detha, the Langa and Mangniyars, among others.

The memoir, like the discussion on the day of the book release, has a wide variety of flavours, not limiting itself to any one ‘right’ way. For example, a memoir is usually associated with the ‘I’ and a personal story but, as Ashok Vajpayee pointed out, Aruna made her memoir not about ‘I’ but about the collective.

In a similar vein, most of us were exposed to the concept of intersectionality in our academic courses, the term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, but it was so insightful when Aruna reflected how even before the term intersectionality was coined, they had been working with an intersectional understanding because the oppression of the women she worked with in rural Rajasthan was not limited to gender identity alone, but also rooted in their being working class and Dalit women.

From the mindless violence of Partition in 1947, the communal carnages of 1984 and 2002, and the Babri Masjid demolition, violence bothers Aruna constantly. As I read, I remembered some incidents. It was 2002. It was a tragic year. Next door to our safe havens of Devdungri and Tilonia, there was a brutal massacre of Muslims in the state of Gujarat. I remember Aruna’s neck marked with deep scabs and psoriasis, a visceral response to the violence.

In that same spirit, when she sensed that I might think of the indiscriminate, brutal attack on the World Trade Center as an act of protest against the vicious US state, the dismay in her voice was clear. She stood against death and all kinds of violence. As she writes in her book, “To crow with happiness and a sense of achievement at the death of anyone is a vulgarity that no kind of moral consciousness should accept as normal.” No wonder the themes of dialogue and non-violence occur repeatedly in her memoir.

The memoir flows like a river. There are chapter titles, but sometimes it feels like we could as well have read in the natural flow, without having to create these artificial divides of chapters. A friend, looking over my shoulder as I re-read the memoir for this article, asked, “If Chapter 8 brings in the ‘MKSS: The Early Years’, then what is the two-thirds of the book you have read so far about?”

A genuine intrigue on his part, but the truth is that from the outside we all see only parts of Aruna’s journey. While some reduce her work and life to the privileged bureaucrat who gave up her plush position to work in rural India, others think of her only as the “RTI activist” who brought in the seminal Right to Information Act. But Aruna cannot be reduced to just the “RTI activist” nor can her memoir be only about the MKSS. From her days as a civil servant to her early memories of the partition, her memoir goes beyond the linearity of time.

The memoir also makes an interesting read for a feminist. Aruna’s repeated pleas to keep hope, to find space for personal anger and angst, and the choice of her title all show her commitment to feminist thought, imbued with a strong sense of justice for caste, class and religion. Aruna writes about the episode of Roop Kanwar’s sati.

Aruna and her colleagues found out about the sati while in a workshop with around 500 women together, and they decided to go to Jaipur to protest. But on the intervening night they discussed the sati. “All agreed that Roop Kawar’s burning was not ‘sat’. As her brother-in-law had lit the funeral pyre,” recounts Aruna. “The small urban group present that evening challenged the women about ‘sat’, saying it was a belief that was not based in fact. The rural women produced fake photos of the sati. The argument was locked in an impasse.

Finally, after hours of simmering discontent, an older woman stood up and said to me, ‘Beta, you believe that a man landed on the moon?’ I said, ‘Yes’. ‘Did you see him there?’ She asked. I answered that I had seen it on TV. ‘You saw a moving photo and believed it; we see photos and believe in them. Let’s leave this argument for now….’” The woman, her point made, then turned to the larger audience and said this was not a time to argue about what proof they had but to understand that Roop Kawar had become a reluctant sati and they should protest and it was decided to march the next day.

In another part of the book, Aruna remembers a first feminist lesson from her mother: how society sometimes describes as ‘labour of love’ what may, in many lived realities, be ‘monotony and tedium’. “When I was around eleven, she advised me never to succumb to pressure to marry and be caught in the cycle of the home and its chores”, writes Aruna. At this point I can’t help but remember that I was lucky to have got extended time with Amma, Hema Jayaram, who lived for several years in Kalimpong, and even in her 80s, when I met her, she was a strong, vibrant person. I remember the stories she shared about her own childhood, how she spoke about her own mother(Aruna’s grandmother) who was deeply involved with social work so that Amma and her siblings were taken along to camps, in different rural areas, depending on where work would take the parents.

At several points in her memoir, Aruna reminisces about and pays tribute to the women who have deeply influenced her. “The women in my life have been mentors and the greatest of friends,” she says. “Conversations with older women, like my mother, and educationist S. Anandalakhmy and Sharada Jain, continue to inform me.”

In Aruna’s book, one also finds a ruthless critique of neoliberalism, state repression and monopoly capitalism. This leads one to think that perhaps she could say more on the structural challenges, as well as possible solutions to the macro problems of our socio-economic and political lives to create new paths for the future. On this count, one felt a bit unsatisfied and wishes for more as Aruna seems to fall back on a solution she has seen work very closely in her own collective struggles, that is “good governance”.

As an activist now geographically embedded in an organisation in eastern India, in rural Bihar, where I live, 1,600 kilometres in a diametrically opposite direction from Aruna’s place of work in the western India, I have often felt that sometimes good governance is not enough. Recently, in the sudden COVID lockdown of 2020, the districts of Araria and Katihar in Bihar were the highest return-migration districts. The lockdown with little notice and preparation was a catastrophe. Yes, it was implemented poorly and without adequate empathy for the poorest individuals by the national and local administrations.

But beyond that, it made me ask, what sort of an economic system forces a majority of the workforce of a certain ‘underdeveloped area’ to work in faraway places anyway? This workforce travels to all kinds of dangerous workplaces, with no social security, not because of the pull factor of good and decent work, but the push factor, i.e. non-availability of dignified, well-paid work in Bihar. Is good governance enough to fix this? Or is there more that needs fixing? What are the new ways of life and work for the future that we need to pursue?

In her critique, Aruna opens a way forward but does not pursue it, though her memoir constantly emphasizes the constitution, democracy and wisdom of ‘ordinary people’ and maybe that is the way forward.

This memoir of ‘doing’ while also reflecting on the ‘doing’ will give strength to new generations to look for macro solutions while getting involved with field-level action.

(Kamayani ‘keki’ Swami is based in Araria, Bihar. She is a founder member of the Jan Jagran Shakti Sangathan (JJSS), an unorganized sector workers union, working in North Bihar. She is currently a Teacher Learner (TL), at the Mosamat Budhiya Jeevanshala (School of Life).)

The memoir 'The Personal is Political' brings the many shades of the activist to light besides offering insights to new generations to look for macro solutions while getting involved in field-level action.

When I pre-ordered my copy of Aruna Roy’s memoir, there was more to it than just a desire for a ‘good’ read. I had spent the first few years of the 21st century working in Rajasthan, with Aruna, on the National Campaign for the People’s Right to Information (NCPRI). In these years, my learning curve was very steep and led me on a journey of social change that I am still part of. So, to read the memoir was a natural desire; but to convince myself to go to the India International Centre for the book release on July 4 was more of a challenge. For one, it meant a two-hour journey from Gurgaon in auto-rickshaws and the Metro, and second, I felt I had seen this life and in some small way had even been part of it. In my smugness, I thought I would have nothing new to gain. Finally, when I did decide to go, I told myself it was only as an act of solidarity. I was pleasantly surprised to be refreshed and re-energised by the discussion that day.

After the book release, as we sat talking, there was a lot of remembering my days with Aruna and the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS), the collective Aruna co-founded. I met a lot of people, some whom I had known as part of my days in Rajasthan, and a larger, eclectic group of people who came from all walks of life – retired civil servants, lawyers, filmmakers, journalists, academics, activists and comrades. But what was the real icing on the cake was to be able to hear the panel discussion, moderated by Ankita Anand, a poet and independent journalist. The panel included powerful women, senior journalist Pamela Philipose, writer Natasha Badhwar and political scientist Niraja Jayal, besides Aruna herself. The sole man on the panel, the writer, literary critic and retired bureaucrat Ashok Vajpayee was also impressive.

As we entered the hall where the book release was to happen, I was expecting the aesthetics, the paintings next to the dais, the beautifully designed backdrop. These were all very ‘Aruna’. But what I was not prepared for was the absence of Aruna’s women friends: Naurati Bai, Chunni Bai, Susheela Bai and many others, who are her co-travelers and who populate the pages of her memoir. However, as the evening progressed, it was clear that all those who were absent were actually present in spirit, and the hall resonated with their stories and a collective journey.

Each panelist brought to life an Aruna we know collectively the one who is an activist and the one who is a connoisseur of classical music. In her many shades, we are as likely to have seen Aruna clad in a handwoven sari, gifted to her by family and friends, protesting at the local administrative office with her friends from rural Rajasthan, as to have seen her enjoying an evening of Indian classical music with people of ‘high’ culture.

She is also the same Aruna who puts on classical music or a selection of folk or bhakti music by the Langa and Mangniyars and walks around the house meditatively putting things in order. Her sense of aesthetics has in no way been compromised by her declassed activist life; whether it be Devdungri or Tilonia, both places that she cohabits with her collective, everyone benefits from her aesthetic sense. This, then, makes it no surprise that her memoir is strewn with quotations from Blake, Tagore, Yeats, Shakespeare, Victor Hugo and many other literary figures. At the same time, you find in her writing the folk wisdom of Kabir, Lao Tzu, Vijay Dan Detha, the Langa and Mangniyars, among others.

The memoir, like the discussion on the day of the book release, has a wide variety of flavours, not limiting itself to any one ‘right’ way. For example, a memoir is usually associated with the ‘I’ and a personal story but, as Ashok Vajpayee pointed out, Aruna made her memoir not about ‘I’ but about the collective.

In a similar vein, most of us were exposed to the concept of intersectionality in our academic courses, the term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, but it was so insightful when Aruna reflected how even before the term intersectionality was coined, they had been working with an intersectional understanding because the oppression of the women she worked with in rural Rajasthan was not limited to gender identity alone, but also rooted in their being working class and Dalit women.

From the mindless violence of Partition in 1947, the communal carnages of 1984 and 2002, and the Babri Masjid demolition, violence bothers Aruna constantly. As I read, I remembered some incidents. It was 2002. It was a tragic year. Next door to our safe havens of Devdungri and Tilonia, there was a brutal massacre of Muslims in the state of Gujarat. I remember Aruna’s neck marked with deep scabs and psoriasis, a visceral response to the violence.

In that same spirit, when she sensed that I might think of the indiscriminate, brutal attack on the World Trade Center as an act of protest against the vicious US state, the dismay in her voice was clear. She stood against death and all kinds of violence. As she writes in her book, “To crow with happiness and a sense of achievement at the death of anyone is a vulgarity that no kind of moral consciousness should accept as normal.” No wonder the themes of dialogue and non-violence occur repeatedly in her memoir.

The memoir flows like a river. There are chapter titles, but sometimes it feels like we could as well have read in the natural flow, without having to create these artificial divides of chapters. A friend, looking over my shoulder as I re-read the memoir for this article, asked, “If Chapter 8 brings in the ‘MKSS: The Early Years’, then what is the two-thirds of the book you have read so far about?”

A genuine intrigue on his part, but the truth is that from the outside we all see only parts of Aruna’s journey. While some reduce her work and life to the privileged bureaucrat who gave up her plush position to work in rural India, others think of her only as the “RTI activist” who brought in the seminal Right to Information Act. But Aruna cannot be reduced to just the “RTI activist” nor can her memoir be only about the MKSS. From her days as a civil servant to her early memories of the partition, her memoir goes beyond the linearity of time.

The memoir also makes an interesting read for a feminist. Aruna’s repeated pleas to keep hope, to find space for personal anger and angst, and the choice of her title all show her commitment to feminist thought, imbued with a strong sense of justice for caste, class and religion. Aruna writes about the episode of Roop Kanwar’s sati.

Aruna and her colleagues found out about the sati while in a workshop with around 500 women together, and they decided to go to Jaipur to protest. But on the intervening night they discussed the sati. “All agreed that Roop Kawar’s burning was not ‘sat’. As her brother-in-law had lit the funeral pyre,” recounts Aruna. “The small urban group present that evening challenged the women about ‘sat’, saying it was a belief that was not based in fact. The rural women produced fake photos of the sati. The argument was locked in an impasse.

Finally, after hours of simmering discontent, an older woman stood up and said to me, ‘Beta, you believe that a man landed on the moon?’ I said, ‘Yes’. ‘Did you see him there?’ She asked. I answered that I had seen it on TV. ‘You saw a moving photo and believed it; we see photos and believe in them. Let’s leave this argument for now….’” The woman, her point made, then turned to the larger audience and said this was not a time to argue about what proof they had but to understand that Roop Kawar had become a reluctant sati and they should protest and it was decided to march the next day.

In another part of the book, Aruna remembers a first feminist lesson from her mother: how society sometimes describes as ‘labour of love’ what may, in many lived realities, be ‘monotony and tedium’. “When I was around eleven, she advised me never to succumb to pressure to marry and be caught in the cycle of the home and its chores”, writes Aruna. At this point I can’t help but remember that I was lucky to have got extended time with Amma, Hema Jayaram, who lived for several years in Kalimpong, and even in her 80s, when I met her, she was a strong, vibrant person. I remember the stories she shared about her own childhood, how she spoke about her own mother(Aruna’s grandmother) who was deeply involved with social work so that Amma and her siblings were taken along to camps, in different rural areas, depending on where work would take the parents.

At several points in her memoir, Aruna reminisces about and pays tribute to the women who have deeply influenced her. “The women in my life have been mentors and the greatest of friends,” she says. “Conversations with older women, like my mother, and educationist S. Anandalakhmy and Sharada Jain, continue to inform me.”

In Aruna’s book, one also finds a ruthless critique of neoliberalism, state repression and monopoly capitalism. This leads one to think that perhaps she could say more on the structural challenges, as well as possible solutions to the macro problems of our socio-economic and political lives to create new paths for the future. On this count, one felt a bit unsatisfied and wishes for more as Aruna seems to fall back on a solution she has seen work very closely in her own collective struggles, that is “good governance”.

As an activist now geographically embedded in an organisation in eastern India, in rural Bihar, where I live, 1,600 kilometres in a diametrically opposite direction from Aruna’s place of work in the western India, I have often felt that sometimes good governance is not enough. Recently, in the sudden COVID lockdown of 2020, the districts of Araria and Katihar in Bihar were the highest return-migration districts. The lockdown with little notice and preparation was a catastrophe. Yes, it was implemented poorly and without adequate empathy for the poorest individuals by the national and local administrations.

But beyond that, it made me ask, what sort of an economic system forces a majority of the workforce of a certain ‘underdeveloped area’ to work in faraway places anyway? This workforce travels to all kinds of dangerous workplaces, with no social security, not because of the pull factor of good and decent work, but the push factor, i.e. non-availability of dignified, well-paid work in Bihar. Is good governance enough to fix this? Or is there more that needs fixing? What are the new ways of life and work for the future that we need to pursue?

In her critique, Aruna opens a way forward but does not pursue it, though her memoir constantly emphasizes the constitution, democracy and wisdom of ‘ordinary people’ and maybe that is the way forward.

This memoir of ‘doing’ while also reflecting on the ‘doing’ will give strength to new generations to look for macro solutions while getting involved with field-level action.

(Kamayani ‘keki’ Swami is based in Araria, Bihar. She is a founder member of the Jan Jagran Shakti Sangathan (JJSS), an unorganized sector workers union, working in North Bihar. She is currently a Teacher Learner (TL), at the Mosamat Budhiya Jeevanshala (School of Life).)