DP Bhattacharya Posted: Oct 12, 2008

Ahmedabad, October 11 The Right to Information (RTI) Act came into force on October 12, 2005. Three years down the line, the Gujarat State Information Commission (SIC) remains one of the most proactive offices in the country, even as activists, the common man as well as the political class have used it to seek information in varied ways. While the law has helped many get access to the information available with the government authorities, it has also been used to serve personal and vested interests in many a case. The Newsline team takes stock of how the use of the RTI Act has fared in the state, detailing important revelations, impacts due to the RTI petitions in Gujarat, candid interview with SIC commissioner R N Das and stories that changed lives, raising hopes, giving fillip to battles in the state.

Delay in disposing complaints a problem area: SIC head

With the Right to Information (RTI) Act completing three years on Sunday, Newsline caught up with Gujarat State Information Commissioner R N Das for a free-wheeling interview. Beyond the Act, he also threw light on resolving the ‘genuine reasons’ which propel citizens to seek information. Often, the stands taken by him have irked the judiciary. Out of the 2,759 cases disposed between October 14, 2005 and March 31, 2008, 133 have been challenged in the High Court.

Das revealed his aspirations, frustrations and observations on the implementation of the people's Act in the state.

* RTI has completed three years. How has the journey been so long in Gujarat?

So far the RTI regime in Gujarat is concerned, I have mixed feelings. The Act has been very successfully implemented in some areas, but the results could have been much better in certain others. What makes me extremely happy is that the Act has percolated to the far-flung areas and the so-called backward districts like Narmada, Dangs and Kutch. I am talking from the number of application that the Commission gets from these districts. A good thing has been that the public authorities have shown a positive attitude towards disclosing information. But people, especially in the rural areas are finding it difficult to use the Act. This needs to be sorted out.

* What are the five biggest hindrances or glitches in implementing RTI in Gujarat?

There are certain difficulties, but it would be unfair to say that those are peculiar to Gujarat alone. Timely disposal of appeals remain a problem area. The Commission does not have enough infrastructure (staff) to effectively deal with the volume of applications.

In all the public bodies, the PIO is already serving in some other capacity. They are entrusted with an additional responsibility, without the additional support which adds on to their burden. As such, the dissemination of information suffers.

The mode of payment for filing an RTI application is either through cash or a DD or a non judicial stamp. While the last option is not available here, quite often one either needs to personally come to the office to pay the fee in cash or spend an additional Rs 20 to make a DD of Rs 20. This needs to be looked into. Despite efforts, awareness about the Act has still not been created in the measure that it should have been.

* What is being done to resolve them?

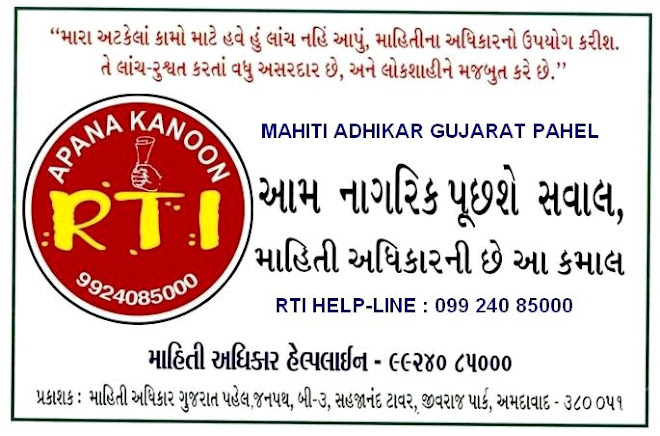

Creating awareness is the job of the government. I am told that the Sardar Patel Institute of Public Administration (SPIPA), which is the nodal organisation for implementing RTI, is conducting a lot of trainings, workshops as a part of the awareness campaign. Besides civil society organisations like the Mahiti Adhikar Gujarat Pahel (MAGP) has been doing a great deal of work like running an RTI help-line and ‘RTI on wheels’ to spread awareness. The combined effort is showing results.

So far as the infrastructure issue is concerned, the state government has already sanctioned 35 additional posts including two commissioners, and we are in the process of getting more people.

* After 3 years, do you think the Act has achieved the goal it initially set out to?

The Act came into force in 2005 with a view to empower the citizens of the country. We cannot judge the efficacy of such a powerful Act within such a short time. If you look into the revolutionary acts like the ‘Freedom of Information Act,’ even in the developed countries, it has taken a lot of time to reach its goal. In a country like ours where there is an interplay of so many forces across the spectrum, it will take time.

* Looking back at last three years, which is one order that makes you feel good?

Personally I feel good about any order that has resolved the genuine reason for which the application had been filed. The Act does not allow the PIO to ask the purpose for filing an application under the RTI. But you have to figure out without asking the petitioner and redress the issue, which had propelled him or her to file the application.

* What has been the lowest point for the Act in Gujarat?

No such point as such, but the Commission is not satisfied with the quality of work it has done so far. Personally I have not been able to discharge my duties to the standards I would have wanted to achieve for myself.

* RTI was to bring about transparency in governance. But critics say it was grossly abused by people to settle personal scores. What are your observations?

This is only partly correct. One must distinguish between settling personal legitimate grievances and settling personal scores. If one gets the sought redressal to one’s genuine legitimate personal grievances through RTI, then that is an achievement. But when an application is filed to harass an officer or a PIO, it becomes a problem. From my experience, such cases are a rarity in Gujarat.

* You have been lauded for a lot of notable orders, but on many occasions, we have seen penalties were avoided, even if the Act called for one. Why so?

Penalty is actually a punishment. The Act asks the Commission to ascertain the cause for failure in furnishing the complete information or furnishing wrong information within the specified time limit. So any proceeding, which may attract a penalty, has to go through meticulous scrutiny. In Gujarat, so far 55 penalties have been ordered. But one should go through each order to find out why penal action was taken.

After going through some cases when we see that the PIO has diligently performed his duty and still could not either provide the required information or got it wrong, the Commission has taken a reasonable view with an intention that the same officer will not repeat the same mistake in future.

* There have been repeated instructions from the Commission for proactive disclosure regarding the government departments. Many of them are, however, yet to provide enough information. What is the commission thinking about it?

Sec 41 (b) of the Act specifically makes Proactive Disclosure an obligation for the Public Authorities. So, every time the Commission has noticed any public authority lacking in this area, it has been ordering for such disclosure. These disclosures, mostly about various developmental schemes, make a lot of differences to the people in the rural areas. In my observations, public authorities do implement our orders on proactive disclosure.

* Many of your orders evoked the wrath of the judiciary. How do you explain this conflict between two legal bodies?

Answer: The law is still evolving; naturally it is a subject of interpretation. So if the Commission has erred, the High Court has taken notice of it.

* What is the status of implementation of RTI in the Judiciary?

You will have to ask them on this.

New-age Renaissance Through Information

RTI landmarks in Gujarat: In a significant order in an application filed by retired IAS officer Premshankar V Bhatt to the Urban Development and Urban Housing Development department under the Gujarat government, the Commission had for the first time asked the concerned department to make the notes made on the files in government offices available to the public in an order dated October 25, 2006.

IAS property returns: Responding to a petition filed by city-based activist Harinesh Pandya, the Information Commission on June 9, 2008 ordered GAD to disclose the annual property returns of an IAS officer.

Saltpan workers got health services at the Little Rann of Kutch after filing an application under the RTI Act. In 2006, Shailesh Patel, from Agariya Heet Rakshak Manch, filed an application seeking information on the details of each of the patients attended by the Comprehensive Mobile health Van Unit in the last six months from Surendranagar district. (This mobile health vans are allotted for health check-up for salt pan workers). His query resulted into regular visits of the vans in the Little Rann of Kutch where the community spends almost eight months to manufacture salt.

Farmers' suicide: Responding to an RTI application filed by city-based activist Bharatsinh Jhala, the Gujarat Police admitted the fact that over 500 farmers committed suicide in the state between January 1, 2003 and October 10, 2007. The information was initially denied to Jhala, after which he approached the Commission, which in turn ordered the police to disclose the information.

Maintenance issue and breaches in Sardar Sarovar Canal network: The Sardar Sarovar Narmada Nigam Limited for the first time on record, admitted to the exact number of breaches in its canal network and also cited the reasons for their damage and leakages. This reply came following an application filed by Vadodara-based activist Rohit Prajapati in the wake of a massive breach at the main Narmada Canal in Mehsana district.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Traditional salt farmers from Little Raan of kutch

VADI VASAHAT- THARAD

RTI ON WHEELS का अनुभव शेर करते हुए माहिती अधिकार स्वयंसेवक सु.श्री.साधना पंड्या

F.D.SCHOOL FOR GIRLS

BHARAT NIRMAN - BY PIB

YUVANINO MIZAZ ANE MAHITI ADHIKAR

Wheels was invited for a demonstration during this workshop. Central Chief Information Commissioner Shri Wajahat Habibullah appreciated this innovation gave his best wishes for future programmes. CIC was keen to know about RTI on Wheels experience in Remote and rural areas.

ON SARKHEJ CROSS-ROAD AHMEDABAD

.JPG)

.JPG)

(COLLECTIVE OF CONCERN CITIZENS AND ORGANISATIONS)

MAHITI ADHIKAR GUJARAT PAHEL

B-3, SAHAJANAND TOWER,

JIVARAJPARK,

AHMEDABAD-380051

GUJARAT

(INDIA)

PANKTI JOG

(Trustee & Executive Secretary)

R T I H E L P - L I N E

0 9 9 2 4 0 8 5 0 0 0

(MON. TO SAT. 11am TO 6pm)

magpgujarat@gmail.com

B-3, SAHAJANAND TOWER,

JIVARAJPARK,

AHMEDABAD-380051

GUJARAT

(INDIA)

PANKTI JOG

(Trustee & Executive Secretary)

R T I H E L P - L I N E

0 9 9 2 4 0 8 5 0 0 0

(MON. TO SAT. 11am TO 6pm)

magpgujarat@gmail.com

APANA KANOON RTI

MYNETA INFO

BLOG ARCHIVE

Search This Blog

TOTAL PAGEVIEWS

RTI ACT 2005

- RTI ACT 2005 (ENG)

- RTI ACT 2005 (URDU)

- RTI ACT 2005 (MARATHI)

- RTI ACT 2005 (BANGLA)

- RTI ACT 2005 (PUJABI)

- RTI ACT 2005 (ORIYA)

- RTI ACT 2005 (KANADA)

- RTI ACT 2005 (TAMIL)

- RTI ACT 2005 (TELUGU)

- RTI ACT 2005 (MALAYALAM)

- RTI ACT 2005 (GUJARATI)

- RTI RULES GUJARAT 2010- ENG

- RTI RULES GUJARAT 2010-GUJ

- RTI 1st APPEAL FORMAT- ENG

IMPORTANT LINKS-1

- 1. Online RTI Portal in States

- 2. Guidelines on implementation of suo-motu disclosure

- 3. Compedium of RTI circulars & notifications by GIC

- 4. Giist of RTI Judgements in Gujarati - Spipa

- 5. Record Retention Schedule (GUJARATI)

- 6. Compendium of Best Practises on RTI (Vol-I)

- 7. RTI-Success Stories: Trust Through Transparency

IMPORTANT LINKS-2

SHOW MY ANSWERSHEET CAMPAIGN SAMPLE RTI APPLICATION

RTI JUDGMENTS

- 1. Dilhi HC - PRESIDENTS SECRETARIAT Vs. NITISH KUMAR TRIPATHI

- 2. Dilhi HC - DISCLOSURE OF COMMUNICATION UNDER RTI, BETWEEN PRESIDENT OF INDIA, AND PRIME MINISTER

- 3. AIR INDIA LTD & ANR Vs. VIRENDER SINGH (DELHI HC LPA—205-2012)

- 4. Bombay HC Nagpur Banch RTI Judgment In LPA No.276/2012

- 5. GUJ HC ON APPOINTMENT OF ADD INFO COMMISSIONER IN WRIT PETITION (PIL)/65/2012

- 6. KARNATAKA HIGH COURT JUD. MANGALORE SEZ Vs KIC: Mangalore SEZ is a public authority and bound to furnish information under Right to Information Act.

- 7. SC RTI JUDGMENT ON QUALIFICATION OF CIC, SIC & APPELLATE AUTHORITIES

- 8. SUPREME COURT ORDER ON Section 8(1) (j)of the RTI Act SLP(C) No. 27734 of 2012, Girish Deshpande Vs. CIC & Ors.

- 9. SUPREME COURT’S JUDGEMENT - Disqualifications for membership of either House of Parliament Legislative Assembly

- 10.Political parties to come under RTI - landmark judgement by CIC

- 11.SC JUDGMENT ON Appointment of Judges as information commissioners

- 12.B’bay HC On RTI & Public Records Act

- 13.RTI DELHI HC JUD- IFFCO is not public authority under RTI

- 14.RTI Jud Delhi HC Attorney general is a public authority, must be under RTI W.P.(C) 1041-2013

- 15.CIC's Order about Private Hospitals

RTI & Voters rights campaign

Traditional salt farmers from Little Raan of kutch

NEW RTI ON WHEELS

RTI TRIBAL YATRA 2013

VADI VASAHAT- THARAD

RTI TRIBAL YATRA 2013

RTI TRIBAL YATRA 2013

RTI TRIBAL YATRA 2013

RTI TRIBAL YATRA 2013

'यशदा' पुणे कार्यशाला

RTI ON WHEELS का अनुभव शेर करते हुए माहिती अधिकार स्वयंसेवक सु.श्री.साधना पंड्या

RTI YOUTH FESTIVAL

F.D.SCHOOL FOR GIRLS

F D SCHOOL FOR GIRLS AHMEDABAD - Youth Fest. RTI

F D SCHOOL FOR GIRLS AHMEDABAD - Youth Fest. RTI

F D SCHOOL FOR GIRLS AHMEDABAD - Youth Fest. RTI

RTI CAMP AT JASDAN GUJARAT

BHARAT NIRMAN - BY PIB

BHARAT NIRMAN SAMMELAN BY PIB

YUVANINO MIZAZ ANE MAHITI ADHIKAR

RTI ON WHEELS AT AMARAIWADI

Central Chief Information CommissionerShri Wajahat Habibullah VISIT RTI on Wheels

Wheels was invited for a demonstration during this workshop. Central Chief Information Commissioner Shri Wajahat Habibullah appreciated this innovation gave his best wishes for future programmes. CIC was keen to know about RTI on Wheels experience in Remote and rural areas.

MAGP TEAM WITH HON. GOVERNOR OF GUJARAT

RTI ON WHEELS AT GOVERNOR HOUSE OF GUJARAT STATE

RTI HORDING BY AHMEDABAD MUNICIPAL CORPORATION

RTI SAMMELAN-2010

RTI ON WHEELS

ON SARKHEJ CROSS-ROAD AHMEDABAD

RTI TALIM OF GOV OFFICER

RTI YATRA IN PANCHMAHAL DISTRICT OF GUJARAT

RTI ON WHEELS IN PANCHMAHAL

RTI ON WHEELS

RTI ON WHEELS AT VILLEGE

RTI ON WHEELS AT COLLEGE