Indian Express: Dheeraj Mishra: New Delhi: Sunday, December 01, 2024.

December 6, 2009: Rajesh Mehto, a migrant worker from Muzaffarpur in Bihar, was called by a private firm to clear sewer garbage at the Delhi State Industrial & Infrastructure Development Corporation (DSIIDC) facility in Patparganj. But Mehto died after inhaling toxic gas in the sewer. The police filed an “Untraced Report” later, claiming they could not find the accused.

EVERYONE NEEDS them but what they need is justice.

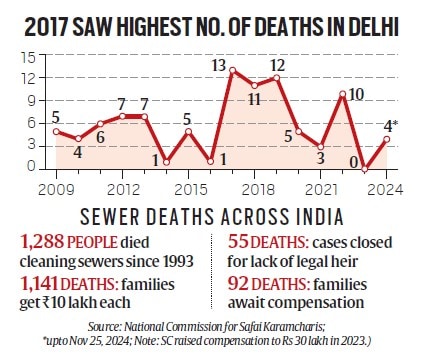

Over the past 15 years, a total of 94 people have died while cleaning sewers in Delhi. But in 75 of those deaths, for which records are available, only one case has led to justice for the victims in the form of a conviction in court, an investigation by The Indian Express of data obtained under the Right To Information (RTI) Act has found.

Records analysed by this newspaper show that only nine of the 38 cases filed in connection with these 75 sewer deaths have been disposed of in court, accounting for a total of 19 lives. They include one conviction, acquittal in two cases, two cases quashed by the High Court, a case of compromise, one closure report, and two cases in which the Delhi Police said the accused could not be traced. The police are yet to challenge the acquittal orders in a higher court, the RTI records show.

For the 75 deaths, the only case since 2009 that led to a conviction involved a site supervisor who was found guilty and sentenced to six months imprisonment for not providing oxygen masks and other safety equipment to the victim before sending him inside a sewer near Sunder Nagar on March 15 that year.

According to records, many of the remaining cases are pending in various Delhi courts for reasons ranging from officers and witnesses not appearing for hearings to lack of adequate staff. Consider this:

📌 In at least three cases, the police told the court they are not able to trace the accused.

📌 In at least two cases, the investigators were not able to obtain the address of the witness.

📌 In at least five cases, witnesses or investigating officers failed to appear regularly in court.

📌 And then there are at least five cases in which the police have not yet completed the investigation and the charge sheet has not been filed.

📌 In some other cases, the court observed that it could not complete the hearing due to lack of staff and cited non-cooperation of senior police officials.

The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act, 2013, bars hazardous cleaning, but there is no specific ban on manual cleaning of sewers and septic tanks as long as protective gear is given. The law specifies 44 types of protective gear, including breath mask, gas monitor and full body wader suit.

“Those who employ people to clean sewers are getting away with brazen impunity. This is a matter of great concern,” said M Venkatesan, chairperson of National Commission for Safai Karamcharis (NCSK), a body of the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment which deals with sewer deaths and manual scavenging.

“Police say they are not able to get evidence in these cases. Suppose, only two people were present at the site — the supervisor and the sanitation worker — and the cleaner died after entering the sewer. Who will prove whether the supervisor had asked the cleaner to go into the sewer or not? For this, some changes are needed in the law. In case of sewer deaths, the FIR should be registered against the commissioner of Municipal Corporation also, then the civic bodies will follow the rules properly. Only when there is accountability for each death, will a signal go right down on following the rules,” Venkatesan said.

A senior official of the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment said it is continuously following up with states on this issue. “It is a matter of concern for the Ministry and it has written to the states for possible intervention to ensure justice in these cases,” said the official.

Records show that overall, Delhi (116) ranks fifth on the sewer deaths count nationally since 1993 when a ban was issued on the practice of manual scavenging.

The RTI records investigated by The Indian Express were obtained from NCSK and Delhi Police. No records were available for ten of the 94 deaths in Delhi since 2009, including two in 2009, four in 2015 and four in 2022. Court records were not available in five other cases accounting for nine deaths: four in 2022, one each in 2021, 2020 and 2016, and two in 2012.

Responding to requests for comment, the Delhi Police acknowledged an email sent by The Indian Express on November 16 and stated that it has been forwarded to the officer concerned. There has been no response since then.

Speaking on the condition of anonymity, a senior Delhi Police officer said there were “several reasons” behind the low conviction rate. “Apart from the lack of any written orders to prove that sanitation workers were asked to enter sewers, there are also informal promises of compensation for the family of the deceased,” the officer said.

“Most victims are from poor families. They choose to settle informally with the contractors for money because they do not have the resources or capacity to fight a legal battle,” the officer said.

The official lack of action, experts say, is telling because many of these sewer deaths occurred at high-profile locations in the national capital, including leading hotels, hospitals and malls.

“All the victims are very poor. At the most, they get compensation, that too because there is a directive from the Supreme Court on this. The provision is that they should get a house, and the government should bear the expenses of their children’s education, but this does not happen,” said Sant Lal Chawariya, the former chairman of Delhi Commission for Safai Karamcharis (DCSK).

“The Commission keeps writing to the government again and again, but no one listens,” he said.

Pointing out that most of the manual scavenging in Delhi is done by members of the SC (Valmiki) community, Chawariya said the “real fight is of caste”. “People do not consider them as human beings, hence do not think about them,” he said.

Take the case of Rajesh Mehto who died in 2009 while cleaning a sewer on the premises of the Delhi government’s DSIIDC in the Patparganj industrial area.

Police records show that after Mehto fell unconscious after inhaling toxic gas, Nar Singh, who was the operator of a sewage pump house for waste water at the facility, and local resident Vijay Kumar jumped in to try and save him. But both fell unconscious. Later, Mehto and Nar Singh were declared dead while Kumar survived.

Records show that the probe led to a private form that was assigned this work by DSIIDC. But years later, Delhi police filed an “Untraced Report” in the case, claiming they could not find the accused.

“The deceased was not in a contract of any kind for cleaning of manhole lines or sewage disposal, etc. No instructions were (there) for him to clean the sewer line. The manhole, where the incident took place, was not part of the pump house. Neither any advice/ written order were issued to the deceased for working there,” reads the police report.