Mumbai Mirror: Mumbai: Sunday, June 24, 2018.

Last week, a

group of about 80 people gathered at a midtown event space in Mumbai for the

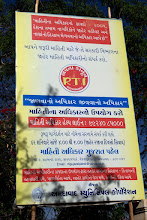

launch of Aruna Roy’s book, The RTI Story. While the book looks back at the

movement led by Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan that led to the passing of the

RTI Act in 2005, uppermost on the minds of many RTI users in attendance were

recent attempts to malign those who file applications Once the floor was thrown

open for questions, a member of the audience stood up and asked Roy what RTI

users could do about recent assertions that most of them are blackmailers.

“Even the BMC

commissioner said it,” the man said, referring to statements that reportedly

emanated the upper echelons of the BMC administration in January following the

Kamala Mills fire. Senior BMC officials reportedly said that some RTI activists

indulged in blackmail and extortion. In addition, the BMC even blacklisted

Praja, an NGO that focuses on good governance, for releasing information

acquired under the RTI Act, claiming that the information had been

misrepresented.

Roy’s answer

was simple: “Ask them for the data. Ask them for a list of names and FIRs. They

won’t be able to give it because it is not true.”

What the

blackmail claims are actually about, say RTI users and civil activists, is

discrediting those who use RTI, which in turn is part of a larger campaign to

undermine the act. “It is a formula to call RTI users blackmailers,” says

Krishna Gupta, who, at 20, is one of the country’s youngest RTI activists.

“This is a tactic to scare people.”

Thirteen

years after the landmark RTI Act was passed an Act that is hailed as one of

the best laws anywhere in the world it has proved to be extraordinarily

impactful. Just this week, news broke that Rs 745.59 crore worth of banned

notes were deposited with the Ahmedabad District Co-operative Bank in the first

five days after Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced demonetisation on

November 8, 2016. This was the largest amount collected by any district

co-operative bank, but what made the news particularly noteworthy was that BJP

president Amit Shah is one of the bank’s directors. The source of information

was an RTI application filed by Manoranjan Roy, a Mumbai RTI activist.

Quite

naturally, the resistance to its provisions from those in authority is growing.

In Maharashtra alone, there were over 41,000 RTI appeals pending as of October

2017, according to a report by the New Delhi-based Satark Nagrik Sangathan and

Centre for Equity Studies. The state also left the post of its chief

information commissioner vacant between May last year and June this year,

before appointing former a former state chief secretary. A study by Moneylife

Foundation, an NGO that engages in advocacy and works on improving financial

literacy, states that 90 per cent of information commissioners are civil

servants, despite the Supreme Court saying back in 2013 that governments must

also look outside the bureaucracy for candidates. Meanwhile, the central

government wants to downgrade the standing of an information commissioner from

that of a judge to a secretary, and is also considering amendments to the Act.

More chillingly, there have reportedly been over 300 attacks against RTI users,

including 51 murders. Maharashtra is the most unsafe state for RTI users, with

10 deaths and two suicides.

But across

India, and especially in Mumbai, citizens are fighting back, and Shailesh

Gandhi, a former central information commissioner who was also part of the

campaign to enact the law, is at the forefront of the resistance. He holds

workshops on the Act for citizens and government agencies, and organises

campaigns in defence of it. After Mehta’s reported comments, he sent a letter

to the BMC commissioner stating, “For too long have RTI users and activists

tolerated the arrogance, pompousness and illegal actions of public servants who

wish to continue as kings and courtiers. You and BMC are consistently insulting

citizens and trying to besmirch a right, which exposes the Municipal

Corporation and its misdeeds.”

According to

Gandhi, the Act is being besieged on three sides. The first is that Public

Information Officers (PIOs) have devised strategies of how not to give

information, the second is the classification of RTI users as blackmailers and

extortionists, and the third is recent rulings passed by the courts. “A lot of

their interpretations are slowly strangling the law,” Gandhi told Mumbai Mirror

in an interview. One such judgment Gandhi refers to is in the Girish

Ramachandra Deshpande case, in which the Supreme Court denied the release of

information relating to the salary of a government official, memos relating to

his censure, details of gifts received and asset and investment information, on

the grounds that it was personal information and, therefore, would amount to

invasion of privacy. According to Professor Sridhar Acharyulu, a sitting central

information commissioner, about 60 per cent of RTI applications are being

rejected citing this order as precedent.

Gandhi calls

the reports of blackmail an out and out lie. He says of the over 20,000 appeals

he has dealt with, there was a problem with “about five percent of them”. In

order to combat such accusations, he hit upon an idea of getting government

bodies to upload RTI applications and their replies on their respective

websites. When Gandhi came across a video of a speech made in the House by Navi

Mumbai corporator Krishna Patkar, in which he accused RTI users of being

extortionists, he called up Patkar, introduced himself and proposed his idea.

He explained that a DoPT circular and a Maharahstra government circular stating

the same idea already existed. According to Gandhi, Patkar agreed to formally

propose it. “If the information is on the website, how will anyone blackmail?”

says Gandhi.

In order to

be more effective and to get numbers, he drafted other RTI users, who were also

concerned by the growing antagonism towards them. Among them were Gupta, who

gives lectures at colleges advising students on how to file RTI applications

and on what issues to pursue; Sunil Ahya, a former electronic goods

manufacturer turned lawyer who has been using RTI for a decade; and Naveen

Saraf, a chartered accountant, who only began using RTI six months ago.

Together, they convinced the corporations of Navi Mumbai, Mira-Bhayander,

Nashik, Yavatmal and a handful of others. Initially, the BMC was not one of

them but on May 4, corporator Alka Ketkar put forth the point of motion in the

house and the resolution was approved. Of course, that’s only the first step.

“The next challenge is getting it implemented and the third challenge, which is

even bigger, is getting it sustained,” says Gandhi.

Sucheta

Dalal, one of the co-founders of Moneylife, set up an RTI centre last year,

thanks to funding the foundation received from whistleblower Dinesh Thakur, who

exposed the data manipulation taking place at drugs manufacturer Ranbaxy. Along

with Gandhi, her foundation is working on creating a database of decisions and

figuring out how government bodies should upload their RTI data. “If all the

information is not put out in a searchable manner, with headnotes and an index,

it is of no use to anyone,” she says.

Gandhi has

already begun collating a set of “positive decisions” from RTI commissioners

that future applicants can use in their own cases, should they go to appeal.

The idea is to create a bank of precedents so that applicants are better able

to argue their side, especially in front of commissioners who might be

sympathetic towards the government.

Gandhi is

also critical of the time it takes for commissioners to handle appeals. While

the law mandates 30 days for Public Information Officers to respond and 30 to

45 days for first appeals to be heard, there is no time limit for second

appeals before a commissioner. “There is no accountability for the

Commissioners but there is a moral responsibility,” says Gandhi.

Every year 40

to 60 lakh RTI applications are filed in India but this is still a tiny

fraction relative to India’s population. In order to increase RTI’s reach,

seminars and workshops are being held across the country. There are websites,

such as RTIIndia.org that provide help to anyone who wants to file an RTI

application (Ahya learned about RTI from the website and today routinely

answers questioned posed by others as a way of paying it back). In Mumbai,

various orgnisations hold workshops, such as Moneylife Foundation and Mahiti

Adhikar Manch, an RTI focused-NGO.

Every

Wednesday evening for two hours, Gandhi holds a seminar at the Moneylife

Foundation in Dadar, where he explains the Act and provides assistance to

anyone who wants to file RTI applications.

At a recent

seminar, Gandhi exhorted a group of law students interning at the Public

Concern for Governance Trust to “avoid question marks” in their applications

because “it will get all tangled up and will take a year.” The students were

mostly interested in water and sanitation issues and Gandhi counselled them to

narrow the focus of their application so the PIOs can’t claim that they are

asking for too much information. “Don’t ask how many inspections were carried

out. Ask for all the inspection reports for the last two years,” Gandhi said.

“Ask for the minimum amount of information but it should be like an arrow.”

Saraf, the

chartered accountant, has attended Gandhi’s seminars at the Moneylife

foundation, and believes there should be many more of them so that people start

to use RTI in their daily lives, such as when applying for a ration card. “If

more people used it, then the government would not be able to undermine it

because they would lose their vote bank,” he says.

Another tool

contained in the pages of the RTI Act, but rarely used, is the right to

inspection. It is a tool that Gupta used to inspect the Temba Hospital (a

government hospital) in Bhayander because he was worried about the level of

care that was available. First, he asked for a list of machinery present at or

allotted to, the hospital. Once he got the list, he filed a second RTI asking

to inspect the hospital under Section 2 (j) of the RTI Act. Armed with the

list, Gupta can be seen alongside hospital staff opening boxes and checking

their contents in a video of the inspection that was uploaded to YouTube. “We

found that either the machines were not working or they were still packed. Very

few machines were working,” Gupta says.

Similarly,

Bhaskar Prabhu, the convenor of Mahiti Adhikar Manch, which networks with

public authorities and runs open houses on how to file RTI applications every

week at St. Joseph’s School in Wadala, encourages the use of the inspection

clause. “People talk about [inspecting] big bridges. You need not do that. Just

do a small ground or a pavement, or whether the storm water drain near you is

cleaned or not,” Prabhu says. He claims if citizens do this, they will be able

to reduce public spending by 20 to 30 per cent.

There is an

inherent tension between the purpose of the Act, which is to disclose

information, and authorities, who prefer to conceal it. At an event on the RTI

organised by Moneylife Foundation last month, which was attended by over 100

people, former Maharahstra chief minister Prithiviraj Chavan said, to much

laughter, that when he was in the DoPT, he was responsible for the legislation,

but “when I came to Mumbai (as CM), I was on the other side and then I wanted

to hide information from coming out.”

This tension

creates a gulf between user and official, says Ahya. “Between government and

the public, there is apprehension on both sides. Citizens think the government

is not doing the right thing and the government thinks the citizen is not

genuine.” However, if this attitude were to change, Ahya says, then it would be

a better experience for everyone and users would be more likely to get the

information they want. According to him, he has never had an unpleasant RTI

experience for that reason. “If people explain things, then you can convince

the other person,” he says. “It should not be personal.”

It is an

approach that Prabhu endorses. “RTI is about bringing in good governance. It

cannot be working against the government,” he says. In other words, there is

more to the RTI than exposing corruption. It can improve efficiency and the

responsiveness of government, providing it is used in that way. “Then the

public authority will understand what is the need for the people,” Prabhu says.

No matter the

party or parties in power, governments have tried to dilute the RTI act ever

since it was passed. The first attempt at amending the Act was made about eight

months after it came into law by the same government that passed it. That

attempt was defeated by public protest and Roy believes the same approach will

be required to stop the current government from amending the act too. “We will

have to go to the streets. It is a war of attrition. We can’t give up.”